- Home

- Denis Hamill

3 Quarters Page 24

3 Quarters Read online

Page 24

She sat there waiting to be taken. Bobby had never liked the idea of taking advantage of liquored-up, emotionally ravaged women. But there were no rules left. He couldn’t trust Sandy. He still thought she might be a plant, sent here by Barnicle to fuck information out of him. Barnicle was probably low enough to order his own woman to use sex to learn what she could from Bobby. The racket must come first.

“Bobby, I don’t want what happened to Dorothea to happen to me and my baby,” Sandy said. She hung her head and softly began to sob. Bobby put the .38 in his pants pocket and lifted Sandy’s chin. Her face was runny with tears. He wanted them to be real.

“No one has really held me in so long I feel like I’m drowning,” Sandy said. “Hold me, Bobby, okay? Just hold me . . . .”

Bobby opened his big arms, and Sandy fell against his chest. He could feel the pressure of her firm breasts. She put her hands around him and hugged him. His hands almost drifted to her buttocks. He stopped himself. She was firm and warm and ready. He lifted her from her feet and laid her on the bed. She lay there, vulnerable. Through a corner of the curtain peeled away from the porthole window, Bobby saw the red tinge of the spire light of the Empire State Building blinking through the rainy city sky.

This was getting harder and harder to do, he thought. He looked down at Sandy and gently pulled the top sheet over her.

“Dorothea doesn’t know how lucky she is,” Sandy said.

“Get some sleep,” Bobby said. “I’ll be out on the sofa.”

“Bobby, promise me that if anything happens to me that my son winds up with my aunt in New Jersey,” Sandy said. “Not with Lou Barnicle . . . please, Bobby . . . .”

“Nothing is going to happen to you or your baby, Sandy. Get some sleep.”

Lou Barnicle sat alone in his brand-new BMW, parked on the rotunda above the Seventy-ninth Street Boat Basin. He lit a Cuban cigar with a gold Tiffany lighter and looked down at the white-and-blue Silverton rocking slightly in slip 99-A. Through the Seco Ni-Tec starlight nightscope, which he gave most of his surveillance operatives, he’d seen the ghostly green image of Sandy Fraser appear on the deck of the boat. He knew that inside the boat she was busy with his enemy.

When she is finished with him, Barnicle thought, I’ll find out what she’s learned and whatever she’s told him.

This Sandy Fraser fell into my life like a gift, he thought. When she stumbled into our three-quarters pension operation at the medical board, the lady lawyer sent her to me for explanations and protection. And eventually I’ll turn the fucking tables on the lawyer, too.

Only one other person has more power in this operation than me. Only The Fixer, that anonymous, obnoxious voice on the phone. Eventually I’ll turn the tables on that pompous prick, too, and run the whole fucking operation. But in the meantime I’ll work for him because he holds the cards. And the money. If I stick to his scam for now, I’ll get more money, status, and power than I ever dreamed possible. Who the fuck could have imagined all this on the day I left the academy thirty years ago with a little tin badge?

Eventually, what I can’t accomplish with the badge, I’ll do with balls and brains on the other side of the badge, Barnicle thought. Because I understand power. These assholes think I’m working for them. But they’ve sat in fucking offices too long, on flat asses, like bean counters, tallying money and not realizing what and who it can buy. I know the miserable fucking streets and the flunkies who are willing to the on them in the name of blind loyalty. The flat asses in the suits just don’t get it—when I work for them, they are really working for me. Me, Lou Barnicle, self-made man, who made his money the old-fashioned way: I stole it. But even beyond the law, these pricks like The Fixer and the lady lawyer think there are rules. Gullible assholes. The law has an Out-of-Order sign hanging off it. The law is out of order.

The only one who could really ruin it all, who can hurt me, stop me, is Bobby Emmet. Only he knows that both sides of the fence are filthy. If I let him stick around, eventually he’ll figure it all out. He survived again this afternoon. Got more lives than a fucking cat with horseshoes up its ass. But maybe it’s for the better. I have to learn to control my temper, submerge my fucking ego. As long as I know what he knows, while he learns it, then Bobby Emmet is working for me, too, without even knowing it.

And Bobby Emmet is a brilliant fucking investigator. More resourceful and more ballsy than any cop I’ve ever met. If I use him right, manipulate him, then whatever he learns about the other scumbags in the scam, about The Fixer and the lawyer and everyone else, I also learn. That’s called leadership. There are just a few more links to connect before I own the whole fucking chain.

Let Bobby Emmet find those missing links, and when he does, he won’t even know he’s been working for me. Me, Lou Barnicle.

I’ll hear from The Fixer in the morning and I’ll tell him this latest piece of news, Barnicle thought. The Fixer will tell me how to proceed.

But tonight, sweet Sandy, be good to Bobby Emmet. While he’s fucking you, I’m really fucking him.

34

THURSDAY

Bobby spent almost two hours of the next morning on line getting the Jeep out of the tow pound on West Street. He paid the $185 tow fine, $50 for illegal parking, and another $645 that Gleason owed in unpaid tickets. He was glad to have the Jeep back. He drove out of the pound to an auto glass shop on Eleventh Avenue and had the rear window replaced for another $150. Another hour of his life, wasted.

At high noon Maggie Emmet stood under the Delacorte Clock dressed in Guess jeans, a Michael Jordan T-shirt, and a pair of white Air Jordans.

“Nothing like rooting for the home team,” Bobby said.

“Michael plays on everyone’s home team,” Maggie said, taking him by the hand and walking south from the clock into the park, readjusting the omnipresent JanSport backpack. “He is ‘The Man.’ Speaking of which, I have a man who wants to meet you. He’s in the parking lot of Tavern on the Green.”

“Who we meeting?”

“Mr. X,” she whispered with histrionic flair, cupping her hands and looking both ways.

He’d learned a long time ago not to probe too deeply with Maggie, who as a preteen kid lived in a fantasy world of intrigue, derring-do, and secret agents. Her mother once dragged the child to a psychologist to find out why she was always talking to herself, sometimes taking a soda bottle into the bathroom and talking to it for hours. Connie was convinced Maggie was disturbed because Bobby was an undercover cop. He was so involved in deception and melodrama that it was affecting their daughter. The shrink told Connie to calm down; Maggie’s behavior was perfectly normal. She just had a fertile fantasy life, and someday she might write fiction or be an actress or something else that required imagination.

Connie was relieved. In her circles the word of a shrink was as infallible as the pope’s.

Bobby followed Maggie through the park, past joggers and dog walkers and young lovers strolling hand in hand.

“You’re doing things you’re not telling me about,” Maggie said. “I’m not a little kid anymore, Dad.”

“No, you certainly aren’t, kiddo,” he said.

“When I was a little kid, you used to tuck me in and tell me stories about all the bad guys you used to lock up and help send away,” Maggie said. “I know half of the stories must have been bull, but now I think a few of them were the real deal.”

Bobby laughed and pushed her. She pushed him back.

“Which parts do you think I, uh, embellished?”

“The parts about the super police dog named Sticky who could actually smell a lie,” Maggie said. “Miniature polygraph in his nose. Could smell it on the saliva when a suspect was lying.”

“I think you were born with a polygraph in your nose.”

“Mom calls it—and I’m quoting her—my bullshit detector,” Maggie said. “And my bullshit detector tells me that you’re not telling me the whole truth, Dad. I know we can’t spend a lot of time together while you�

��re trying to clear your name. I’ve lived without you long enough to handle that a while longer. But I want you to be honest about what’s going down. I’m scared, Dad. For you. For me. I can’t stand the idea of losing you again.”

His daughter had gone through a physical puberty and a mental evolution in the time he was away. The second part of it accelerated by a public trial, headlines, trash TV, and separation. She had always been precocious, but now talking to Maggie was like talking to an adult. Still, he had to be careful: she had an adult mind controlled by a teenager’s emotional circuit board.

“Look,” Bobby said, “some of the stuff you found out for me has already helped me put big pieces of this puzzle together. I’m your old man, but you are still a kid. So I’m gonna tell you what I think you can handle.”

“Okay,” she said.

So as they walked through the park, he told her about Barnicle, Tuzio, and Farrell, possibly all working together in a pension scam to raise money for the Stone for Governor Campaign. “These two cops, Kuzak and Zeke, collect the money and the three-quarters pension applications. The money goes to the Stone campaign. The applications wind up at the police medical board in Rego Park, Queens. Maybe you can find out who’s on that board so I can check them out.”

Maggie said she would. Then Bobby made her swear she wouldn’t repeat any of this to anyone, including her mom or Trevor. He told her that when he started asking questions about this racket a year and a half ago, they framed him for Dorothea’s murder. He didn’t tell her about the meeting he’d had with her mother and left out the part about the cops trying to kill him out in Rockaway and the attack on the boat. He did tell her about Tom Larkin and Carlos at the Brooklyn crematorium and the medical examiner whom he would see on Friday. He told her a little about Gleason and how well Herbie could cook. He didn’t tell her about Sandy and the baby with the mystery father. But at some point, he thought, Maggie should meet Sandy. The girl’s intuitive take on Sandy might be better than his.

“Okay,” Maggie said. “My bullshit detector tells me you’re telling me the truth. At least I know you’re making some progress.”

She stopped in front of a bench just down the hillock from the parking lot of Tavern on the Green. “Trevor bought me this amazing new IBM notebook with built-in cellular modem and miniature printer,” she said, removing the small, three-pound compact piece of wizardry from the JanSport bag. “Thanks to satellites, I can access and download from just about anywhere in the universe except the subway, which Mom wouldn’t let me take anyway. That’s another story. But I have a few things I want to check . . .”

She took out a bagful of software discs labeled “Department of Motor Vehicles,” “FBI,” “NYPD,” and started shuffling through them.

“How much did Trevor spend on that thing?” Bobby asked, feeling a tinge of inadequacy, a dent in his macho armor.

“Chill, old man,” Maggie said. “It’s just a thing, Dad.” She hefted the little computer. “A tool. Meanwhile, he’s up there waiting to speak to you.”

“Who?”

She pointed up the knoll to Trevor Sawyer, leaning on his Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud limousine, checking his gold Rolex.

“He signed me out of summer school for lunch on the proviso that I bring you to see him,” Maggie said, with the IBM notebook opened on her lap, punching keys on the elaborate keyboard. “You’re wasting time. Go see him, and then he’ll take me back to school. I’ll be okay right here.”

Bobby climbed the hillock and shook hands with Trevor Sawyer. His uniformed chauffeur sat inside the Rolls-Royce and rolled up the windows as Bobby approached. Father and stepfather stood with their backs to the car, keeping Maggie in plain sight.

“I’d like to pay you for that gizmo you bought her,” Bobby said, pulling from his pocket what was left of the five-thousand-dollar wad of cash Gleason had given him.

“Please, don’t insult me,” Trevor said. “Your kid’s love isn’t for sale. In fact, the quickest way to Maggie Emmet’s heart is through yours.”

Bobby felt abashed, crumpled the wad of money in his hand, and looked from Trevor to Maggie. He said, “Sorry. I’m not trying to insult you. It’s just . . . She’s my kid and I want to pay . . .”

“Please, Bobby,” Trevor said. “I was born into the filthy shit. I’m not here about money. Not yours anyway.”

Bobby shoved the money back into his pocket, satisfied that he’d made the feeble, awkward gesture. He didn’t want to like Trevor. Everything in his being said he should loathe this man who slept with the woman he used to love, who lived under the same roof with his only child. But Trevor just seemed like a nice fella, in spite of his shitty money. Still, how could you ever trust someone who never dreamed of winning the lottery?

“The best part of marrying Constance—”

“Is that really what Connie wants to be called now?”

“It’s how she introduced herself,” Trevor said. “It’s hard to call her anything else. I wish it was ‘Connie.’ Or ‘Dot’ or ‘Mousie’ or ‘LuLu,’ something sweeter. But anyway, the best part of marrying her was Maggie’s arrival in my life. She let me know from jump street, as she would say, that if I wanted to be her friend, I’d have to help her father who was jammed up—”

It finally clicked. He glanced at Maggie, fiddling with her laptop.

“You put up my bail, didn’t you?” Bobby said. “You contacted Gleason . . . .”

“It was the least I could do,” Trevor said, loosening his tie as the sun dialed its way toward the hottest hour of the day. “And don’t start reaching for the damned money again. My bail is safe. I know as long as Maggie is around, you aren’t going anywhere.”

Bobby was really glad now that he had turned down Connie’s amorous offer. This guy didn’t deserve to be cuckolded. On the other hand, he could have bailed me out to have me whacked out here, he thought.

“This what you wanted to see me about?” Bobby asked.

Trevor smiled. “No. I wanted to tell you about a party I went to in Luke Worthington’s apartment the other day . . . .”

“The big Republican fund-raiser?”

“The one and only,” Trevor said. “Of course, I give to both sides. Constance refuses to go to political events. So I brought my checkbook. However, this gathering was odd. More than a hundred people, food, a string quartet, champagne. But no one asked for a cent. The primary is six days away, the race is neck and neck. Stone is saturating the airwaves with ads, but I don’t know where his campaign is getting its money. None of the usual suspects—and I’m one of them—are being hit on. It’s as if they wanted to send a signal: a Stone administration will be indebted to no one.”

Bobby knew where Stone for Governor was getting some of its money but said nothing. Was Trevor sniffing to see what he knew, Bobby wondered.

“That doesn’t sound like the worst idea in politics,” Bobby said. “But what’s all this have to do with me?”

“Well, Sol Diamond was there, of course,” he said. “And Daniel Barth . . .”

“The little bulldog-looking media guru?”

“Yes, that’s him,” Trevor said. “Anyway, as I nosymoseyed toward Worthington’s study to see what new paintings he’d bought lately, I heard Diamond and Barth involved in a rather hushed but agitated discussion of your case. I stopped in the foyer and listened. I’m a nosy swine like that. Barth is a genius, but he’s a hothead and he’s too fond of Jack Daniel’s—the drink, not the person—and he was lashing into Diamond about how your case was handled. About how you got out on bail. Diamond tried to explain that it was a Democratic-stacked appellate court that overturned the conviction. He actually said, ‘Unlike Brooklyn judges, I can’t control appellate judges.’ Barth chided him for taking too long to schedule a new trial, how they could all feel the political reverberations for a long time to come if it wasn’t tidied up pronto.”

“What did Diamond say?” Bobby asked.

“Well, he was trying to tell Barth tha

t it wasn’t the time or place to discuss this,” Trevor said. “Diamond said they were trying to get your case on the calendar ASAP. Then Diamond tried to walk away, nip the conversation in the bud. But Barth grabbed him and asked when the brand-new charge would be lodged, one that would revoke your bail.”

“What new charge?” There was a blade of fear in Bobby’s voice.

“I don’t know,” Trevor said. “I wanted to ask you. Because, at that point Diamond was so angry he just stormed out of the study and left the party. I ducked into the dining room before he could see me. A few minutes later, some aides whisked Barth out as well. He was a little too drunk for everyone’s good. It was a delightfully nasty little piece of business. And, I thought, one significant enough that I should pass it on to you in person. The purpose being, watch your ass. I think they might be looking to frame you for something new, in addition to your lady friend’s . . . death.”

“Thanks,” Bobby said, wondering if this was a warning coming from him.

“I don’t want to see that little girl hurt any more,” Trevor said, nodding down toward Maggie, who was still working the notebook computer.

They shook hands, and Bobby thanked him for being so kind to his daughter and for the information. Before Bobby turned to walk back to Maggie, Trevor said, “One more thing.”

“Yeah?”

“The other day on the boat,” Trevor said. “Thanks for not flicking my wife.”

Bobby stared at him in disbelief.

“You spied on us?” Bobby was incredulous, didn’t know whether to be angry at Trevor or himself for not realizing that the Japanese tourist with the video camera was a tail.

Trevor smiled and said, “I always have someone keeping an eye on my assets. For whatever reason, you didn’t reclaim my wife. For that I owe you a lasting gratitude. I love Constance and want our marriage to work.”

“She loves you, too,” Bobby lied. “So you’ve been in touch with Izzy Gleason all along?”

“He’s quite the character, isn’t he?” Trevor said. “I had warned him that if I thought you would interfere with my marriage when you were out, I would do everything in my power to have you sent back to jail. He assured me you were an honorable man. I called him the other day, when you lived up to that honor, to say if there was anything else I could do, that I would. He said there was something I could do. . . .”

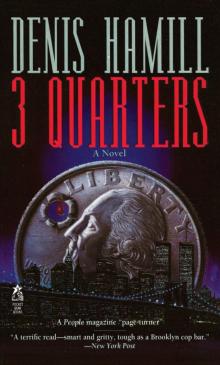

3 Quarters

3 Quarters