- Home

- Denis Hamill

3 Quarters Page 25

3 Quarters Read online

Page 25

“What was that?”

“He asked if I could set him up with Naomi Campbell,” Trevor said. “Do you think he was serious?”

“Oh, he was serious all right,” Bobby said with a smile.

“I must give him some work down the line if I can ever find anything suitable to his particular type of law,” Trevor said.

“I don’t wish that on you,” Bobby said.

“Send Maggie up for the ride back to school,” Trevor said. “If Constance knew I’d taken her out to see you, she’d be livid because of all the tabloid reporters. So keep this little rendezvous under your hat. Anything you need, call.”

Trevor climbed into the back of the limousine and closed the door. Bobby liked him even more now than he had before. Which made him trust him even less.

Bobby called to Maggie, and she folded her computer notebook, put it back into the JanSport bag, and held a long scroll of printed paper in her right hand. When she reached Bobby, he put his hand around her shoulder.

“I forgot to tell you that one of Dorothea’s girlfriends visited me,” Bobby said. “I don’t know what she knows or if I can trust her. Her name is Sandy.”

“Let me meet her, Dad,” she said. “I’ll check her out for ya.”

“I was thinking the same thing,” Bobby said.

“Make it Coney Island on Saturday,” Maggie said. “The Cyclone, Nathan’s hot dogs, Wonder Wheel. Like old times.”

Only a rotten divorce and a little dash of murder could make a fourteen-year-old talk about the good old days.

“A deal,” Bobby said.

Maggie handed Bobby the printed sheets from her IBM computer.

“What’s this?”

“The names and brief bios of the three doctors on the police medical board you told me about,” Maggie said. “Public record. Wasn’t anything in the New York Times, so I checked the back issues of The Civil Service Gazette, which is on-line. I found a story about the medical board. Story says two of those three doctors have to approve each medical pension.”

Bobby looked from Maggie to the printout news story, then back to his kid.

“You’re some piece of work,” Bobby said.

“Adore ya,” she said, kissing his cheek as she climbed into the back of the limo. “Gonna be late. Bye.”

“Love ya, kiddo,” Bobby said as the limo pulled away. Then he studied the printout, focused on the name and smudgy photo of a young doctor named Hector Perez.

35

Bobby stared up at Tom Larkin, who was swinging from the ceiling. A pair of handcuffs were yoked around his purpled neck. His belt was looped through the two metal handcuff hoops and tied to an overhead water pipe. His mouth was puffy with cotton and gauze, his eyes demented in death. A trash barrel lay on its side on the floor of the men’s room as if he had stood on it before it was kicked out from under him.

Bobby had seen the crowd and the flashing lights before he reached the Kopper Kettle. The diner was on Fourth Avenue, three blocks from the 72nd Precinct, where Tom Larkin worked. Bobby was supposed to meet him here at four PM. It was 4:08. Larkin must have arrived early.

While Bobby was parking his Jeep, he’d noticed Max Roth in the crowd, scribbling into a notebook. The new crime scene had not yet been taped off, and Roth had led Bobby through the parking lot, behind the diner, to a spot where they could look through the open men’s room window.

Now, the crowd was beginning to swell, and uniformed cops and plainclothes detectives were starting to push people back. A morgue wagon pulled up. The NYPD criminalists and a forensic crew would soon scour the men’s room for clues, taking pictures, dusting for fingerprints, taking measurements.

“I was doing some of that research you asked me to do down in the Brooklyn courthouse when I got a beep saying a cop named Larkin had committed suicide here,” Roth said. “I drove right out. By the way, I found out that both Farrell and Tuzio once clerked for Judge Mark White.”

“My judge?”

“Yep,” Roth said. “These two graduated college together, like you said, and then they were sucked right into Brooklyn politics. It was a good hunch on your part to see if they worked together.”

“I never expected it to be for the same judge,” Bobby said. “The one who sentenced me. I gotta tell Gleason . . . .”

“Remember, I get first dibs on this story, Bobby,” Roth said.

“Of course,” Bobby said. “But wait till Gleason says it’s okay.”

“Fine. Meanwhile I gotta write this fast for deadline.”

Bobby widened his eyes and stared up at Larkin. “No way he committed suicide,” Bobby said softly.

“Why’s that?”

“See the gauze in his mouth,” Bobby said, pointing to Larkin’s mouth.

“To muffle his screams?”

“He had a root canal this morning and still went to work,” Bobby said.

“You sure about the root canal?”

“I was supposed to meet him here at four this afternoon, Max,” Bobby said. “He was excited about some news he had for me.”

“He met his maker first,” Max said.

The Internal Affairs guys were busy interviewing a few cops who had been dining and who were still on the scene. Bobby stood in the parking lot of the diner, quietly telling Roth about his final message from Tom Larkin. “He said something about an old kidnapping case involving someone named Kate Clementine,” Bobby said. “Somehow connected to a missing architect. The Ukraine . . . .”

“Was Larkin on painkillers for his bad tooth?” Roth asked. “This sound like pretty stream-of-consciousness stuff.”

“But please don’t mention that in the column either until we check it out,” Bobby said.

“The Kate Clementine thing sounds familiar to me,” Roth said, tapping his right temple with his Bic pen. “But I think it goes way back.”

“Seventeen years,” Bobby said. “Check it out, Max, will ya? Also see if you guys ran any stories on some missing architect. More recent. Maybe a Ukrainian architect. I don’t know . . . .”

“The Clementine thing would be before the paper had computers,” Roth said. “I’ll check the clips, but it’ll take some time. Right now I gotta get as much here as quickly as I can and dump it into the paper.”

An investigator from the medical examiner’s office closed the men’s room window, blocking the ghastly view of Tom Larkin. It reminded Bobby that he still had to see the assistant ME named Franz. Bobby was feeling empty, hollow, slightly nauseous. He had contaminated someone else now. It had gotten his father’s friend killed.

The black IAB detective that Bobby recognized as Forrest Morgan walked up to them.

“The Bobbsey twins,” he said. “One leaks; the other pisses. Into print.”

“Nice to see you, too, Morgan,” Bobby said.

“Is that quote on or off the record, Morgan?” Roth asked.

“What the hell are you doing here, Bobby?” Morgan asked. “I’ll need a statement from your sorry ass.”

“I need one from you,” Roth said to him.

“No comment,” Morgan said.

“Same here,” Bobby said. “I’m not on the job anymore. So why would I want to talk to NYPD Internal Affairs? As a private citizen, I’ll talk to Homicide if you want.”

“Right now it’s being treated as a suicide,” Morgan said. “The handcuffs around his throat were his, had his initials scratched into them. The belt was his . . .”

Roth wrote these details into his reporter’s notebook with the Bic pen. No serious reporter ever carried an expensive pen on assignment. They always disappeared before the story made print.

“So was the root canal he had this morning,” Bobby said. “Who bothers to get a root canal if you’re gonna commit suicide? He had a girlfriend he was crazy about. Said he was gonna propose. He had two years to retirement. Larkin didn’t hang up, Morgan.”

“I’m using that root canal bit,” Roth said, still scribbling in his notebook.

“No, you’re not,” Morgan said.

“Excuse me, did someone also lynch the First Amendment in this diner? Because if they did, I’d sure like to report that, too.”

“I told you nice not to write that,” Morgan said, stepping past Bobby and staring into Max Roth’s eyes like a warden to a con.

“I’m telling you that I have an obligation,” Roth said.

Bobby stepped in front of Morgan, who was trying to intimidate Roth. “Why don’t me and you walk around the block,” Bobby said.

Morgan looked from Roth to Bobby and sidestepped past the newspaperman, and Bobby followed, catching stride with him.

“I don’t like that nasty little man,” Morgan said.

“He’s a columnist,” Bobby said. “If everyone liked him, he wouldn’t be doing his job. Sort of like working Internal Affairs.”

Morgan gave him a sideways glance, smiled, nodded.

“All right, I hear that,” Morgan said as they strolled down toward Third Avenue, over which ran the rusting Gowanus Expressway, thundering with trucks and cars. “But I’m trying to do an investigation, and your buddy is fucking it up.”

“If he doesn’t get it down as a possible murder, which I know it is, then nothing will happen,” Bobby said. “I liked Tom Larkin, liked him a lot. He was one of the few guys on the job who believed in me.”

“Not the only one,” Morgan said. “I don’t think you killed that girl.”

“Thanks,” Bobby said. “But you never stepped forward.”

“For what? How was I gonna help you? I’m disliked in my own community for being a cop. I’m disliked by cops for being IAB. I’m disliked in IAB for being black and ‘off agenda.’ You can’t get any more nigger than a black IAB cop, baby. But it’s what I do. And I do it well. And it still doesn’t get me any promotions. So, I don’t see how I could have helped your case. First, it was handled by Homicide and then the Brooklyn DA’s office. It wasn’t an internal police matter. But what I saw in your file, and I looked the same way I look at the old fight films, they didn’t make a good case against you. Just like you never really beat me. But you went the distance four times. And anyone as good with his hands as you are would never use a knife. Especially on a woman. Some things just don’t jibe.”

They walked along Third Avenue, under the highway that cut this neighborhood in half. A group of Hispanic men sat on plastic milk crates playing dominoes on the traffic island amid the rusted hulks of abandoned and crashed cars. As they strolled, Bobby told Morgan as much as he thought the big cop could digest in one feeding. Without naming names. He told him about the three-quarters pension scam, about certain cop bars where the pension papers and the cash were picked up, about a corrupt assistant district attorney, and defense attorney, a private security firm that ran a mini-militia of corrupt three-quarters cops.

“I think you need me now as much as I need you,” Morgan said. “What other cop you gonna call?”

Morgan was itchy for names and hard facts. But Bobby was cagey, just tantalizing him with a sketch, doing a rope-a-dope, inviting his old opponent onto the ropes with him. Bobby wanted him salivating for a later time, when he would need an ally.

“I’ve been trying to crack open the three-quarters scam for years,” Morgan said. “We’ve nailed plenty of individual phonies, of course. Guys weight-lifting with bad backs. Arrogant assholes with three-quarters fighting in the Golden Gloves! But I’ve suspected for some time that there was some kind of an organized crew. Now, if you’re saying these same people are associated with Tom Larkin’s death, then maybe me and you have some more serious talking to do.”

“We do, but I’m fighting this one by my rules, Morgan,” Bobby said. “My ass is on the line here. My life. I have a kid I might never see on this side of prison bars again. And the woman I love is missing. I have to know I can trust somebody before I can confide in him.”

“You can trust me,” Morgan said as they circled back to the parking lot of the diner. The parking lot was now filled with uniformed cops from the 72nd Precinct. Bobby noticed Caputo and Dixon in the crowd. Bobby’s Jeep was now covered with dozens of thin slices of American cheese, melting in the late summer sun.

“That’s the sign of a rat,” Morgan said. “A cheese eater.”

“I know what it means,” Bobby said. “Talking to you only confirms it for them.”

“You want protection?” Morgan asked.

“Yeah, from you?” Bobby laughed. “You butted me in the last round of our last fight.”

“That was a goddamn accident,” Morgan said, angry and insulted. “I never fought dirty in my life. Never had to.”

“With these people you might have to,” Bobby said.

“This is different,” Morgan said. “Dirty cops are my business. They’re worse than ordinary mutts. They’re skells who hide behind a badge. That ain’t fair and makes them mutts times two. And if they don’t fight fair, why should I?”

“Aw shit, I knew the butt was an accident,” Bobby said. “I just wanted to hear you say it, Forrest. You never apologized for it.”

“Why should I apologize?” Morgan said, incredulous. “The judges gave you the decision even though I won.”

“You won? Are you crazy? I won every fucking round.”

“You ran like a rabbit,” Morgan said.

“I boxed your ears off,” Bobby said.

“We could do it again,” Morgan said, stopping in his tracks, nodding his head, fists balling, serious.

“If I climb back in the ring with you,” Bobby said, “we’ll be fighting side by side.”

“I hear that,” Morgan said. “But get it straight. I’m not your friend. I ain’t your enemy, either. That’s the way it got to be in my job.”

“Sounds fair,” Bobby said.

“Now, can you keep this Max Roth from printing the shit about Larkin’s root canal?”

“No,” Bobby said. “He’s already on the way back to the office, dictating it in from the car phone.”

“This could fuck things up,” Morgan said.

“I think we need to make people sweat,” Bobby said. “I also want you to note for the record that I’ve been told I might be set up and framed for another crime. What and who or where—I obviously don’t know.”

“You gonna give me some names?”

“When the time is right,” Bobby said. “Meanwhile, I think you have a whole precinct to interview. I was you, I’d start with a couple of shitheads named Caputo and Dixon. They didn’t exactly get along with Tom Larkin. I wouldn’t bet they were regular contributors to the United Negro College Fund, either. If you catch my drift.”

Forrest Morgan wrote down the two names, and Bobby held out his hand for him to shake. Morgan looked down at it and said, “I’ll do that when you’re ready to come out fighting.”

36

Bobby recognized William Franz as soon as he saw him walk in from his six PM snack break. Bobby had been waiting for almost a half hour in the lobby of the Brooklyn medical examiner’s office of Kings County Hospital. Over the years, especially in the crack-infested eighties, Kings County had become like a MASH unit in a war zone. It was also the hospital where Bobby’s father, Sean Emmet, was officially pronounced dead, all those years ago.

Working on cases, Bobby had been here too many times. Somewhere downstairs Tom Larkin’s body was probably in a zipper bag in a walk-in freezer, waiting to be cut open for autopsy.

The ME’s office was at ground level, but the autopsy rooms were in the cool, discreet basement. Most of the crime victims who died in ER were shipped downstairs to the morgue. Bobby had seen them: people who had been killed in shootings, bludgeonings, overdoses, poisonings, knifings. They all wound up on the stainless-steel tabletops there, cut from hip to hip, nipple to nipple, and then straight down the center of the torso, opened up like human envelopes, the elaborate contents examined for causes of death.

But in the case of the cremated woman whom the authorities convinced a jur

y was Dorothea, there was no body to cut, no brain to explore. Just a pile of beige dust. But Carlos from the crematorium had also given the Brooklyn deputy chief ME, William Franz, the charred but intact teeth that had survived the final flames. Bobby wanted to know what had happened to them.

Bobby remembered Franz from the days when Bobby was still a cop with Brooklyn South Narcotics and often brought the chubby, bespectacled little man NYPD forms to sign in connection with various cheap homicides. Not much talk, just bureaucratic cop-to-ME formalities. Bobby remembered him for his high-pitched laugh and for always smelling of onions—of the hot-clog-with-everything-on-it variety. He’d hate to witness Franz’s own autopsy. Now Bobby rose to greet Franz, who still smelled of onions. He wore blackframed glasses with lenses as deep as glass bricks.

“Ah,” Franz said, rocking a toothpick in his mouth as he walked with short, quick paces past a female receptionist, “I was wondering when you’d get around to me, Mr. Emmet.”

He waved to the receptionist and a hospital security guard and said, “He’s okay.”

Bobby followed him through a heavy metal door. Franz grabbed two white lab coats from a wall hook, tossing one to Bobby and pulling on his own as he clicked down a hospital-green corridor to another door. Bobby then trailed Franz down a flight of steps and was immediately overwhelmed by the smell of formaldehyde and death.

“You remember me from the old days, Brooklyn South?” Bobby asked. “Or the goddamned newspapers?”

“Cops’ faces I don’t remember,” Franz said, inspecting the tip of the toothpick for salvage. “Killers I do. So tell me, did you kill her?”

He stopped on the stairs and turned and smiled at Bobby through thick lenses. Buried deep in the distorted wavy abyss behind the glasses were two little dark, dilated eyes.

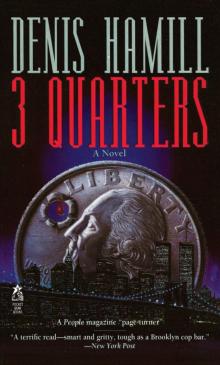

3 Quarters

3 Quarters